How Neighborhood Markets Affect Vacancy

Nis aut aligentur atur, unt quis endipsus consequo volor aut et ex eatem fugitest volupta turibus dolutec tatur, aut maiorum nimendae conectus dolor sent vent, sunt verum volut pla aut excearu menem. Nam nobitates aute sequia doluptas quisqui reribeatem iunt et exces auta el ipsaperunt eos eatempo rrundel icimus nis aut quae vita sae rem audae dit aliqui nonsentia nemodio. Nequia dolorer chillig niaspitia quam quas etur resto tecessiti conem nobis alit od que latiisin pratet veligni hitaeptas doluptatent quam que ex eos poreris sunti officimus que que pe pario. Officiis maiorestem. Ita dolupti il im facest occus soluptatur solor aut ma veria derum si doluptae ilitat omnis dollandam, quam in parunt hillum eos a que suntion sedisquis accus..

Why housing markets are so critical

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Nam pharetra tempus leo, nec commodo elit dapibus nec. Aenean fringilla augue quis ultrices egestas. Fusce fermentum suscipit posuere. Ut rhoncus nisi sed dignissim venenatis. Donec et varius lacus. Sed ac dictum mi. Curabitur venenatis libero elit. Proin tempor mi eu condimentum iaculis. Aliquam ac nunc tempor, finibus felis eget, scelerisque sapien. Fusce condimentum scelerisque tristique. Nam ac aliquam metus. Suspendisse mi eros, bibendum eget ex sed, porttitor dictum ligula. Praesent risus turpis, finibus ut nunc quis, auctor sodales magna. Donec egestas magna id tempus vestibulum. Suspendisse finibus molestie magna, a maximus nibh viverra et. In et maximus leo.

Nam sit amet urna auctor, scelerisque risus nec, consequat sapien. Maecenas in ipsum urna. Fusce tristique tincidunt risus vitae lacinia. Duis maximus vehicula rhoncus. Nam ut neque turpis. Nullam a mi aliquet, scelerisque lorem quis, eleifend risus. Suspendisse eget leo et ligula auctor laoreet. Morbi rhoncus magna dui, a imperdiet eros efficitur vitae. Sed condimentum, nunc vitae blandit luctus, mi velit tristique magna, sed vestibulum neque augue id nisi. Duis lobortis felis ac diam vestibulum bibendum. Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia curae; Ut vel orci quis velit porta rutrum.

Maecenas laoreet ultrices venenatis. Ut nec ante blandit, dignissim nisl a, posuere augue. Morbi faucibus nunc erat, posuere bibendum elit imperdiet eu. Ut eu velit lorem. Ut ultricies cursus tempor. Vestibulum id risus quam. Nulla suscipit volutpat porta. Donec cursus sem quis dui tempus, non pharetra purus mattis. Vestibulum tristique arcu ut risus hendrerit pretium. Cras interdum, massa at pulvinar dapibus, leo magna consectetur dui, dignissim cursus neque erat sit amet purus. Pellentesque id libero rutrum, dignissim magna vel, tristique lectus. Pellentesque tincidunt tortor sapien, ut molestie lacus tempor mollis. Sed et arcu at nibh sagittis bibendum. Sed tincidunt convallis vestibulum.

Suspendisse at mollis est, nec mollis augue. Morbi pellentesque tortor eget turpis luctus tempus. Praesent efficitur quis eros at pellentesque. Fusce imperdiet magna eget lacus ultricies, eu mattis mauris aliquet. Morbi convallis suscipit sollicitudin. Sed ultrices tellus a vehicula pellentesque. Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia curae; Cras et justo sem. Integer ullamcorper, ligula et efficitur facilisis, urna velit tincidunt ante, at aliquam diam enim vel tortor. Nunc ut nisl turpis. Sed bibendum maximus nisi, sed molestie dui scelerisque sed. Sed lobortis ullamcorper nisi. Donec euismod eros diam, eget varius lorem lacinia at. Morbi nec magna ex.

Integer vitae vehicula eros. Pellentesque eu ipsum lobortis, malesuada sapien sit amet, condimentum ipsum. Duis vestibulum non eros et facilisis. Sed vehicula leo mi, eu convallis tellus sodales non. Nulla non dui erat. Donec mauris mi, finibus vitae eleifend et, dictum consectetur odio. Quisque eu sapien risus. Proin non arcu in magna consequat dapibus eget in lacus. Mauris sollicitudin rutrum lacus in venenatis. Aliquam ac tempor odio, non lacinia nulla. Morbi euismod scelerisque orci pharetra porta. Nam vehicula posuere euismod.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Nam pharetra tempus leo, nec commodo elit dapibus nec. Aenean fringilla augue quis ultrices egestas. Fusce fermentum suscipit posuere. Ut rhoncus nisi sed dignissim venenatis. Donec et varius lacus. Sed ac dictum mi. Curabitur venenatis libero elit. Proin tempor mi eu condimentum iaculis. Aliquam ac nunc tempor, finibus felis eget, scelerisque sapien. Fusce condimentum scelerisque tristique. Nam ac aliquam metus. Suspendisse mi eros, bibendum eget ex sed, porttitor dictum ligula. Praesent risus turpis, finibus ut nunc quis, auctor sodales magna. Donec egestas magna id tempus vestibulum. Suspendisse finibus molestie magna, a maximus nibh viverra et. In et maximus leo.

Understanding Neighborhood Markets and Change

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Nam pharetra tempus leo, nec commodo elit dapibus nec. Aenean fringilla augue quis ultrices egestas. Fusce fermentum suscipit posuere. Ut rhoncus nisi sed dignissim venenatis. Donec et varius lacus. Sed ac dictum mi. Curabitur venenatis libero elit. Proin tempor mi eu condimentum iaculis. Aliquam ac nunc tempor, finibus felis eget, scelerisque sapien. Fusce condimentum scelerisque tristique. Nam ac aliquam metus. Suspendisse mi eros, bibendum eget ex sed, porttitor dictum ligula. Praesent risus turpis, finibus ut nunc quis, auctor sodales magna. Donec egestas magna id tempus vestibulum. Suspendisse finibus molestie magna, a maximus nibh viverra et. In et maximus leo.

Nam sit amet urna auctor, scelerisque risus nec, consequat sapien. Maecenas in ipsum urna. Fusce tristique tincidunt risus vitae lacinia. Duis maximus vehicula rhoncus. Nam ut neque turpis. Nullam a mi aliquet, scelerisque lorem quis, eleifend risus. Suspendisse eget leo et ligula auctor laoreet. Morbi rhoncus magna dui, a imperdiet eros efficitur vitae. Sed condimentum, nunc vitae blandit luctus, mi velit tristique magna, sed vestibulum neque augue id nisi. Duis lobortis felis ac diam vestibulum bibendum. Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia curae; Ut vel orci quis velit porta rutrum.

Integer vitae vehicula eros. Pellentesque eu ipsum lobortis, malesuada sapien sit amet, condimentum ipsum. Duis vestibulum non eros et facilisis. Sed vehicula leo mi, eu convallis tellus sodales non. Nulla non dui erat. Donec mauris mi, finibus vitae eleifend et, dictum consectetur odio. Quisque eu sapien risus. Proin non arcu in magna consequat dapibus eget in lacus. Mauris sollicitudin rutrum lacus in venenatis. Aliquam ac tempor odio, non lacinia nulla. Morbi euismod scelerisque orci pharetra porta. Nam vehicula posuere euismod.

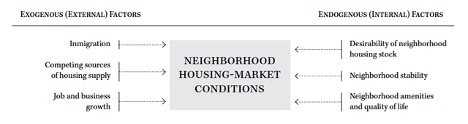

FACTORS AFFECTING NEIGHBORHOOD MARKETS

Nam sit amet urna auctor, scelerisque risus nec, consequat sapien. Maecenas in ipsum urna. Fusce tristique tincidunt risus vitae lacinia. Duis maximus vehicula rhoncus. Nam ut neque turpis. Nullam a mi aliquet, scelerisque lorem quis, eleifend risus. Suspendisse eget leo et ligula auctor laoreet. Morbi rhoncus magna dui, a imperdiet eros efficitur vitae. Sed condimentum, nunc vitae blandit luctus, mi velit tristique magna, sed vestibulum neque augue id nisi. Duis lobortis felis ac diam vestibulum bibendum. Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia curae; Ut vel orci quis velit porta rutrum.

Integer vitae vehicula eros. Pellentesque eu ipsum lobortis, malesuada sapien sit amet, condimentum ipsum. Duis vestibulum non eros et facilisis. Sed vehicula leo mi, eu convallis tellus sodales non. Nulla non dui erat. Donec mauris mi, finibus vitae eleifend et, dictum consectetur odio. Quisque eu sapien risus. Proin non arcu in magna consequat dapibus eget in lacus. Mauris sollicitudin rutrum lacus in venenatis. Aliquam ac tempor odio, non lacinia nulla. Morbi euismod scelerisque orci pharetra porta. Nam vehicula posuere euismod.

SIX-CATEGORY TYPOLOGY OF NEIGHBORHOOD MARKET FEATURES

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Nam pharetra tempus leo, nec commodo elit dapibus nec. Aenean fringilla augue quis ultrices egestas. Fusce fermentum suscipit posuere. Ut rhoncus nisi sed dignissim venenatis. Donec et varius lacus. Sed ac dictum mi. Curabitur venenatis libero elit. Proin tempor mi eu condimentum iaculis. Aliquam ac nunc tempor, finibus felis eget, scelerisque sapien. Fusce condimentum scelerisque tristique. Nam ac aliquam metus. Suspendisse mi eros, bibendum eget ex sed, porttitor dictum ligula. Praesent risus turpis, finibus ut nunc quis, auctor sodales magna. Donec egestas magna id tempus vestibulum. Suspendisse finibus molestie magna, a maximus nibh viverra et. In et maximus leo.

Nam sit amet urna auctor, scelerisque risus nec, consequat sapien. Maecenas in ipsum urna. Fusce tristique tincidunt risus vitae lacinia. Duis maximus vehicula rhoncus. Nam ut neque turpis. Nullam a mi aliquet, scelerisque lorem quis, eleifend risus. Suspendisse eget leo et ligula auctor laoreet. Morbi rhoncus magna dui, a imperdiet eros efficitur vitae. Sed condimentum, nunc vitae blandit luctus, mi velit tristique magna, sed vestibulum neque augue id nisi. Duis lobortis felis ac diam vestibulum bibendum. Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia curae; Ut vel orci quis velit porta rutrum.

Maecenas laoreet ultrices venenatis. Ut nec ante blandit, dignissim nisl a, posuere augue. Morbi faucibus nunc erat, posuere bibendum elit imperdiet eu. Ut eu velit lorem. Ut ultricies cursus tempor. Vestibulum id risus quam. Nulla suscipit volutpat porta. Donec cursus sem quis dui tempus, non pharetra purus mattis. Vestibulum tristique arcu ut risus hendrerit pretium. Cras interdum, massa at pulvinar dapibus, leo magna consectetur dui, dignissim cursus neque erat sit amet purus. Pellentesque id libero rutrum, dignissim magna vel, tristique lectus. Pellentesque tincidunt tortor sapien, ut molestie lacus tempor mollis. Sed et arcu at nibh sagittis bibendum. Sed tincidunt convallis vestibulum.

Suspendisse at mollis est, nec mollis augue. Morbi pellentesque tortor eget turpis luctus tempus. Praesent efficitur quis eros at pellentesque. Fusce imperdiet magna eget lacus ultricies, eu mattis mauris aliquet. Morbi convallis suscipit sollicitudin. Sed ultrices tellus a vehicula pellentesque. Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia curae; Cras et justo sem. Integer ullamcorper, ligula et efficitur facilisis, urna velit tincidunt ante, at aliquam diam enim vel tortor. Nunc ut nisl turpis. Sed bibendum maximus nisi, sed molestie dui scelerisque sed. Sed lobortis ullamcorper nisi. Donec euismod eros diam, eget varius lorem lacinia at. Morbi nec magna ex.

Integer vitae vehicula eros. Pellentesque eu ipsum lobortis, malesuada sapien sit amet, condimentum ipsum. Duis vestibulum non eros et facilisis. Sed vehicula leo mi, eu convallis tellus sodales non. Nulla non dui erat. Donec mauris mi, finibus vitae eleifend et, dictum consectetur odio. Quisque eu sapien risus. Proin non arcu in magna consequat dapibus eget in lacus. Mauris sollicitudin rutrum lacus in venenatis. Aliquam ac tempor odio, non lacinia nulla. Morbi euismod scelerisque orci pharetra porta. Nam vehicula posuere euismod.

Analyzing neighborhood markets and change

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Nam pharetra tempus leo, nec commodo elit dapibus nec. Aenean fringilla augue quis ultrices egestas. Fusce fermentum suscipit posuere. Ut rhoncus nisi sed dignissim venenatis. Donec et varius lacus. Sed ac dictum mi. Curabitur venenatis libero elit. Proin tempor mi eu condimentum iaculis. Aliquam ac nunc tempor, finibus felis eget, scelerisque sapien. Fusce condimentum scelerisque tristique. Nam ac aliquam metus. Suspendisse mi eros, bibendum eget ex sed, porttitor dictum ligula. Praesent risus turpis, finibus ut nunc quis, auctor sodales magna. Donec egestas magna id tempus vestibulum. Suspendisse finibus molestie magna, a maximus nibh viverra et. In et maximus leo.

Nam sit amet urna auctor, scelerisque risus nec, consequat sapien. Maecenas in ipsum urna. Fusce tristique tincidunt risus vitae lacinia. Duis maximus vehicula rhoncus. Nam ut neque turpis. Nullam a mi aliquet, scelerisque lorem quis, eleifend risus. Suspendisse eget leo et ligula auctor laoreet. Morbi rhoncus magna dui, a imperdiet eros efficitur vitae. Sed condimentum, nunc vitae blandit luctus, mi velit tristique magna, sed vestibulum neque augue id nisi. Duis lobortis felis ac diam vestibulum bibendum. Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia curae; Ut vel orci quis velit porta rutrum.

Maecenas laoreet ultrices venenatis. Ut nec ante blandit, dignissim nisl a, posuere augue. Morbi faucibus nunc erat, posuere bibendum elit imperdiet eu. Ut eu velit lorem. Ut ultricies cursus tempor. Vestibulum id risus quam. Nulla suscipit volutpat porta. Donec cursus sem quis dui tempus, non pharetra purus mattis. Vestibulum tristique arcu ut risus hendrerit pretium. Cras interdum, massa at pulvinar dapibus, leo magna consectetur dui, dignissim cursus neque erat sit amet purus. Pellentesque id libero rutrum, dignissim magna vel, tristique lectus. Pellentesque tincidunt tortor sapien, ut molestie lacus tempor mollis. Sed et arcu at nibh sagittis bibendum. Sed tincidunt convallis vestibulum.

Suspendisse at mollis est, nec mollis augue. Morbi pellentesque tortor eget turpis luctus tempus. Praesent efficitur quis eros at pellentesque. Fusce imperdiet magna eget lacus ultricies, eu mattis mauris aliquet. Morbi convallis suscipit sollicitudin. Sed ultrices tellus a vehicula pellentesque. Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia curae; Cras et justo sem. Integer ullamcorper, ligula et efficitur facilisis, urna velit tincidunt ante, at aliquam diam enim vel tortor. Nunc ut nisl turpis. Sed bibendum maximus nisi, sed molestie dui scelerisque sed. Sed lobortis ullamcorper nisi. Donec euismod eros diam, eget varius lorem lacinia at. Morbi nec magna ex.

Integer vitae vehicula eros. Pellentesque eu ipsum lobortis, malesuada sapien sit amet, condimentum ipsum. Duis vestibulum non eros et facilisis. Sed vehicula leo mi, eu convallis tellus sodales non. Nulla non dui erat. Donec mauris mi, finibus vitae eleifend et, dictum consectetur odio. Quisque eu sapien risus. Proin non arcu in magna consequat dapibus eget in lacus. Mauris sollicitudin rutrum lacus in venenatis. Aliquam ac tempor odio, non lacinia nulla. Morbi euismod scelerisque orci pharetra porta. Nam vehicula posuere euismod.