Strategically Demolish No Styling

IN THIS SECTION

When property owners refuse to fix up their property, governments may need to step in to demolish a property to protect the health, safety, and welfare of its citizens. Over the past few decades, cities faced with widespread vacancy have spent hundreds of millions of dollars demolishing properties. Despite this investment, many cities still saw vacancies rise. This is because demolition alone cannot fix widespread weak demand.

Demolition must be used as a strategic tool within a border equitable revitalization strategy, or the pipeline of properties in need of demolition will never yield. This section provides an overview of key questions communities should contemplate while they develop a vacant property strategy.

What is demolition?

Demolishing a building that has stood for many years can be a difficult, even controversial, decision. This is even more so when the building has historical value or cultural significance, or contains architectural features or craftsmanship that are rarely seen today. Demolition, however, is inevitable in many situations; thoughtfully and responsibly carried out, it can be an important part of the process by which communities can achieve equitable revitalization.

While this section is using the term “demolition” for simplicity’s sake, it is important to know that there are many methods whereby which a building’s materials can be removed from a site and our use of that term is intended to encompass all of those methods. A common method is using heavy machinery to knock down a building and dispose of all the materials in a landfill, what is traditionally called “demolition.” For the past couple of decades, many cities have chosen instead to salvage or recycle materials during the removal process to reduce environmental harm, increase the supply of building materials, and support local economies. This method is known as “deconstruction.”

Methods of deconstruction vary widely – from quick removal of architecturally unique or high value items to fully disassembling the whole structure by hand. Accordingly, the cost and time for deconstruction varies as do the environmental benefits.

To learn more about deconstruction and its benefits, see these resources:

- Delta Institute’s Deconstruction & Building Material Reuse: A Tool For Local Governments & Economic Development Practitioners

- Build Reuse

- Michigan State University’s Center for Community And Economic Development, Domicology

- EPA Residential Demolition Recycling Resources and Deconstruction Rapid Assessment Tool

Why is demolition needed?

There are several reasons why a community may feel that structure removal is necessary.

The supply of buildings may exceed demand.

In communities that have been experiencing long term population and job loss resulting in widespread or hypervacancy, there is a structural imbalance between supply and demand. The supply of properties greatly outpaces the demand for those properties. This is one of a number of reasons why large-scale demolition may be needed.

Market demand in cities like Detroit, Cleveland or Baltimore has not been great enough to keep the supply of houses in productive use. Even as demolition has reduced the supply in softer markets, demand has continued to drop. This is a long-term trend in most of these cities. Between 1960 and 2000 Detroit removed 178,000 dwelling units or 32 percent of its 1960 housing stock, while the number of vacant houses and vacant lots steadily increased. Many places experienced an acceleration in vacancy in the early 2000s due to mortgage and tax foreclosures, which increased the flow of properties into abandonment over and above that which would have resulted from long-term declines in demand.

Abandoned buildings trigger major negative impacts

Vacant, abandoned buildings devastate their surroundings, and the community as a whole. Their presence in a municipality, neighborhood or block imposes both social and economic costs for municipalities and their residents, providing further justification for strategic demolition. The public cost of maintaining vacant and abandoned buildings is high; when coupled with the loss of revenues associated with these properties, this leads to a significant fiscal drain on local government. Abandoned buildings also result in reduced municipal revenues, not only from the buildings themselves, but also from the diminution of the value of properties around them.

These impacts are modest compared to the intangible effects of vacant properties. They undermine the vitality and quality of life of the city’s neighborhoods, while discouraging the revitalization of cities and neighborhoods. Their presence raises a powerful issue of social justice: Is it fair that lower-income households should see their modest wealth diminished, their personal security compromised and the prospects of their neighborhoods harmed, as a result of circumstances utterly outside their control? Abandoned buildings consistently rank at or near the top of neighborhood problems identified by residents of lower-income neighborhoods.

To read about the impacts of vacant and deteriorated properties, click here.

VIEW IFRAME EMBED

VIEW VIDEO EMBED

Demolition can mitigate the impacts of abandonment.

There is little research directly comparing the impacts of vacant lots to that of vacant buildings, but there appear to be clear differences in favor of vacant lots. Under most conditions, vacant lots as such have less of a harming influence than a vacant building, they pose far fewer dangers in terms of criminal activity and fire risk, are likely to result in less cost to the city and the adjacent owner and, most importantly, can more readily be turned into an asset – or at least a neutral factor – for the neighborhood in circumstances where resources and market conditions make it impossible to maintain or reuse the existing inventory of houses and other buildings.

Moreover, vacant lots can be far more easily maintained by neighborhood residents and other volunteers. As the work of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society in Philadelphia has shown, vacant lot stabilization, which is a modest and inexpensive treatment of a vacant lot with simple plantings and fencing, can all but eliminate dumping. A study by Susan Wachter of the University of Pennsylvania found that such treatments of vacant lots in Philadelphia’s Kensington neighborhood “result(ed) in surrounding housing values increasing by as much as 30 percent.”

- Go to the Wachter study, The Determinants of Neighborhood Transformation in Philadelphia: Identification and Analysis – The New Kensington Pilot Study.

- Learn more about the impacts of vacant land stewardship

Vacant lots lend themselves to inexpensive reuse options that do not exist for vacant buildings, which as a rule can only be reused through total rehabilitation. Vacant lots can be sold to adjacent homeowners for side lots – often an attractive option in tightly-built urban neighborhoods – or used for community gardens, play areas, or restoration of natural spaces. To learn more about vacant land reuse options and policies and practices to support large-scale vacant land reuse, visit our Vacant Land Stewardship Online Resource Center.

How to balance demolition versus preservation?

A controversial issue in many communities is the tension between demolition and preservation of older buildings. Although the arguments for demolition summarized above are strong, it is also true that demolition can lead to the loss of historically, culturally, and architecturally valuable buildings and undermine the physical texture of neighborhoods or commercial districts. This can not only have potentially destructive effects on their vitality and potential for revitalization, but can lead to the loss of valuable links to the city’s cultural identity and historic legacy. These are not insignificant considerations.

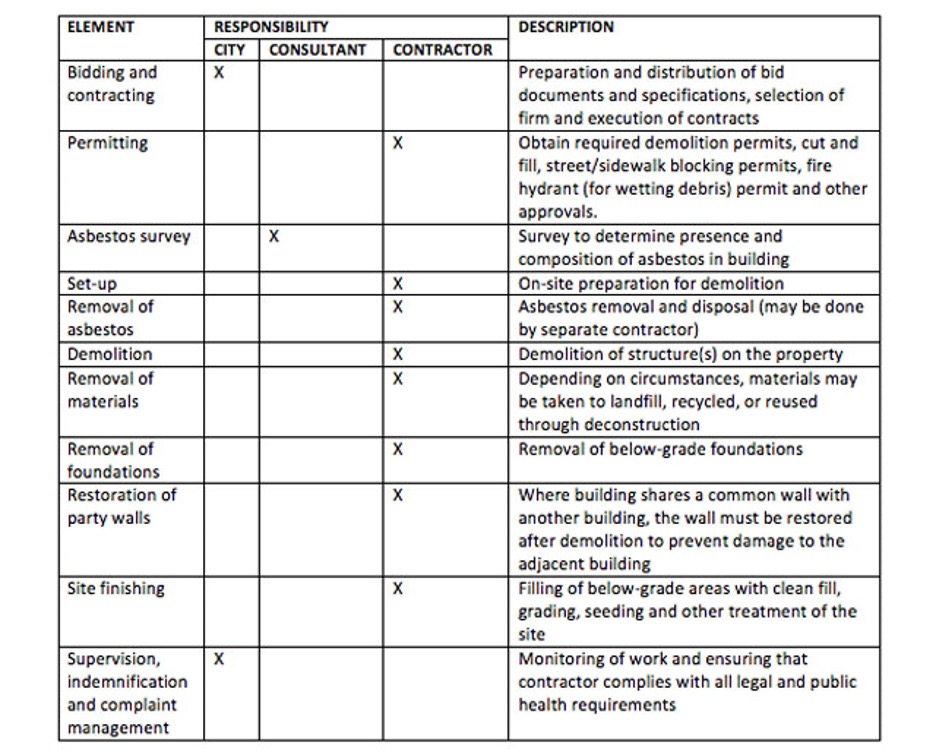

There is not one single metric that will tip the scale in towards demolition or preservation. Communities should take into consideration a multitude of factors when determining the best outcome for the property, the table below lists some of these key considerations for communities with widespread vacancy.

It is also possible that a building leans towards a preservation outcome, however, financial resources are not yet sufficient to rehabilitate that property, either because the underlying market is still strengthening or because the local community is working to generate enough subsidy to make rehabilitation happen. In these cases, a community could “mothball” a property to prevent further damage while a property awaits rehabilitation. Mothballing goes beyond throwing up a few pieces of plywood on broken windows. It is a process that focuses on structural stabilization and maintenance of the property. This could include some key repairs to reinforce structural integrity, eradicating vermin, securing the property from vandalism and moisture while allowing ventilation, winterize and/or disconnecting utilities, and providing for ongoing maintenance. For a mothball check list, see here.

Planners, public officials, community leaders and historic preservationists must be creative in how they think about preservation in the light of the painful realities of excess demand and ongoing harm from vacant, abandoned buildings. It may be more valuable to focus on preservation as a means of preserving critical neighborhoods, in the social and economic as well as physical sense, rather than preserving buildings exclusively as artifacts, often outside of their historic and spatial context; as historic preservation consultant Ned Kaufman writes, “the heritage ‘object’ – the core value to be protected – is the urban community as a living entity.”

What is Strategic Demolition?

When demolition is needed, it should take place in a targeted, strategic fashion. Municipalities and others carrying out ongoing demolition programs should use their funds cost-effectively, maximize their ability to recover costs from property owners, and integrate demolition activity with other revitalization strategies to increase the benefit to the neighborhoods and the community as a whole. Demolition strategies should build in three elements:

- Apply rational criteria for choosing which buildings should be demolished and which retained;

- Link demolition targets and priorities with specific stabilization, redevelopment and reuse goals and strategies; and

- Engage key players to ensure that decisions take all relevant considerations and perspectives into account.

How to choose which buildings to demolish

Most distressed communities have far more structures that are potential candidates for demolition than resources with which to demolish properties. Depending on the building itself, its relationship to other buildings around it, the characteristics of the neighborhood in which it is located and the nature of other activities planned or taking place in the surrounding area, any given building may or may not be a suitable candidate for demolition.

Decisions must also take into account the larger economic context. In a neighborhood with very weak market conditions and severely limited market demand, it may be acceptable to demolish buildings even though the outcome will be vacant lots. In a neighborhood with strong market demand, knowing that there is a specific reuse proposal or at least reuse potential for that lot may be an important consideration.

Many demolition decisions will not be clear-cut, but will involve a balancing of many different factors, and the level of market demand may tip the balance in one direction or the other. The choice of which buildings to demolish, other than emergency demolitions, should be made through a “decision screen” or “decision tree” that enables decision-makers to weigh the various factors for or against demolition of any specific building.

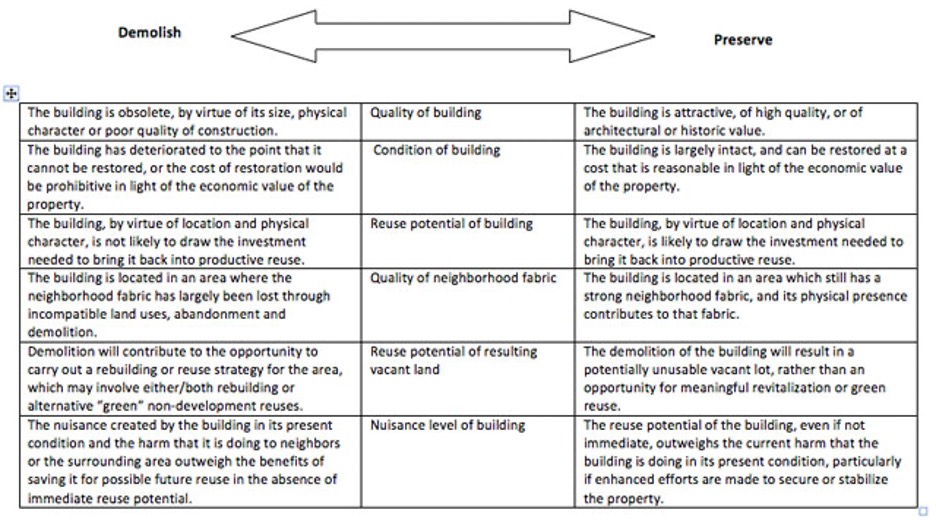

The table below lists the factors that could be considered in making a decision to demolish a residential building. The subsequent residential demolition “decision tree” illustrates how the factors shown in the table can be organized into a framework for decision-making. While this table and decision tree are for residential structures, similar approaches could be taken for commercial and industrial properties.

In the end, however, these assessments and decision models are only tools, which can assist in decision-making, but cannot substitute for the exercise of informed, thoughtful judgment.

While most of the factors in the table above are largely self-explanatory, the subject of physical texture, as it is called in the table, and its relationship to the demolition decision, is worth further discussion.

Every neighborhood has a particular texture, made up of its buildings, their relationship to one another and to the spaces between them. In the best cases, found not only in historic neighborhoods, but also in many traditional neighborhoods in communities around the country, buildings and spaces form a harmonious whole or ensemble. The buildings are not identical, but they share enough common features to blend into a whole that “fits together” in an observer’s eyes. The balance between buildings and open spaces, which urban designers refer to as the “rhythm” of buildings and spaces (or solids and voids), also contributes to this feeling of appropriateness.

In many areas, however, the harmonious texture that once existed has been impaired or compromised, or in some cases, may never have truly existed. Buildings may have been demolished or destroyed over the years and replaced by incompatible buildings, such as a gas station in the middle of a Victorian-era shopping street, or a ranch house faced with aluminum siding in the middle of a block of large 1920s brick houses. Parking lots or used car dealerships may appear on vacant lots between clusters of row houses. In many parts of distressed older communities, so many houses have been abandoned and subsequently demolished that there is no residential texture left. There are many blocks in cities like Detroit or Buffalo where only a handful of houses remain, standing in a sea of vacant land.

It is important to evaluate how demolishing a particular building will affect the texture of its block or area, because the quality of that texture is an important factor in the stability and revitalization potential of the block and neighborhood. In a largely abandoned area, this is not likely to be an issue. In areas which still have a distinctive texture, however, particularly where that texture is widely perceived as contributing significantly to the neighborhood’s quality, it becomes an important consideration. In such cases, despite the cost involved, stabilizing or “mothballing” vacant buildings for which a use is not currently available may be a source strategy. In order to address these issues, it is important to have a planner or urban designer and a historic preservation professional, as well as residents of the neighborhood involved in the demolition decision-making process.

This decision tree comes from Bringing Buildings Back, which contains a more extended discussion of demolition as well.

How to set demolition priorities?

Once a community has gone through the previous exercises to determine which of their vacant properties should be demolished or preserved, if that community has wide-spread vacancy, they have likely generated a list of demolition properties that far outstrips their current resources to demolish properties.

Communities will have to choose how to prioritize which demolitions happen over time – which are urgent, and which can wait. Communities should not demolish whichever property is next in the queue, nor should they “spread the peanut butter” by randomly choosing a property in each area of the community. While those might be politically palatable approaches, they are shortsighted and neither will result in neighborhood-level change.

Communities need to develop strategic priorities to guide their demolition activities. No system of priorities should be so all-encompassing or rigid to prevent individual demolitions that may be urgently needed for some reason from taking place. These should, however, be the exception, and not be so numerous that they distract local government and residents from the goals of the larger strategy.

Priorities should take into account:

- Market and other neighborhood conditions;

- Other activities taking place in the same area; and

- How much the abandoned buildings are affecting the vitality and sustainability of the block and area where they are located.

Once it has been determined that demolition is the appropriate strategy, below are some principles for designing a demolition priority system.

Demolishing a single building on one block where it is the only derelict structure may have more impact with respect to resident confidence, property values and future tax revenues than demolishing ten buildings elsewhere. This suggests that in most cases priority should be given not to demolition in the most heavily abandoned and disinvested areas or demolition of the “100 worst buildings,” but to areas where removal of buildings is likely to help stabilize neighborhood conditions and property values and create potential reuse opportunities. Following this principle, specific priorities can be determined by linking demolition to neighborhood stabilization criteria and activities.

Priority for demolition in heavily disinvested areas should focus on locations where there are specific reuse potentials that can be furthered by demolition. Reuse should not be limited to development in the traditional sense but can include any of a number of different green reuse strategies that will make the land a community asset even in the absence of market demand.

Once the city has identified those neighborhoods and areas which meet minimum threshold levels of physical and economic condition, it should develop a plan for strategic demolition in those areas. This should begin with identifying other key neighborhood features or activities:

- A strong social fabric, reflected in strong neighborhood or civic associations or neighborhood-level institutions;

- Active community development corporation- or local developer-led stabilization or revitalization activities, preferably but not necessarily grounded in a neighborhood or target area plan;

- Features that suggest greater market potential, such as a distinctive housing stock or location in close proximity to a strong anchor institution; and

- A significant planned public investment in an area, such as a new school or transit station.

Demolition priorities should be connected as much as possible to other activities that are taking place either in the area as a whole or targeted to a smaller area within a larger neighborhood. If a new school is being built in the neighborhood, for example, it may be appropriate to prioritize the blocks immediately surrounding the school, or the blocks that represent the principal pathways for children and visitors to the school. Timing is critical. In this example, the demolition should be completed before the new school opens its doors. Similar, where a municipality or CDC is carrying out a neighborhood stabilization program, or where private market construction or rehabilitation is starting to take place, it is important to prioritize demolition for the particular blocks where these activities are going on to the end that, when new or rehabilitated housing is being marketed, no vacant, abandoned buildings would still be standing to blight the same block face or immediate area and discourage homebuyers.

Once the key target area has been identified, to the extent possible all of the buildings in that area that cannot be reused should be demolished. If there are three derelict abandoned buildings on a block face and two are demolished, the remaining abandoned property will continue to do almost as much harm as the three that previously stood there.

Because the process of setting priorities depends on understanding many different factors, including market conditions, ongoing stabilization activities, and community needs, key players both inside and outside municipal government need to be engaged, to ensure that decisions take all relevant considerations and perspectives into account.

How to Engage Key Players in Demolition Decisions?

If buildings targeted for demolition are to be selected on the basis of rational criteria, and if demolition activity is to be prioritized and linked strategically to other revitalization and redevelopment activities, the process of making strategic demolition decisions needs to be opened up to those who have the skills and knowledge to apply those criteria, and who are aware of and engaged in revitalization activities in the community. Realistically, whatever their skills and commitment, the public officials directly responsible for carrying out demolitions may not have the full range of knowledge or background in all of the relevant areas to make those decisions most responsibly.

Municipal officials must lead the process, since they have the ultimate legal authority and responsibility to act. They should seek information and input from representatives of community development corporations and other entities engaged in neighborhood planning or revitalization, as well as representatives of neighborhood associations in areas potentially targeted for demolition, to help identify priorities and neighborhood strategies as well as evaluate specific buildings.

Municipalities should establish a formal standing committee on demolition, or a less formal working group that nonetheless meets regularly to review proposed demolitions. A procedure to ensure that disagreements between municipal departments are expeditiously resolved should be in place; the building official or other individual responsible for carrying out demolitions should not have the authority, however, simply to override the positions of other municipal agencies. The process itself should be designed so that prospective demolitions can be reviewed and approved in advance of formal action, so that the building official can maintain a pipeline of approved demolitions to take to bid as funds permit.

The process should be designed so that it does not impede timely and cost-effective demolition or impede the use of demolition as a law enforcement matter where necessary to address urgent health and safety concerns. Those matters have to be dealt with expeditiously and are appropriately the exclusive purview of the responsible public officials.

What are good demolition practices

Before getting into the nuts and bolts of practices, municipalities need to decide which benefits matter most for their community – what their demolition guiding principles are. To paraphrase a partner of ours, when it comes to demolition practices, you can have it done fast, well, or cheaply, but you can’t have all three. Communities need to decide what’s most important to them.

For example, a community might want to do “wet-wet-wet demolition” where the building is sprayed with water prior to demolition, during demolition, and the materials are sprayed before leaving the site. This practice suppresses the dust emerging from the process, which could contain lead and may exacerbate health conditions like asthma. Or a community might want to do deconstruction which also reduces dust exposure. However, these steps add time or cost, and if a community has said that their highest priority is to take as many properties down as cheaply and quickly as possible, these practices are at odds with that priority.

Once a community has figured out which properties need demolition, how they are going to prioritize demolition, and what their guiding principles are, they can design their demolition practices.

This section summarizes the key nuts-and-bolts issues that add up to good demolition practices. The more demolitions that a community does – or wants to be able to do – the more important it is to have systems that get the most out of every demolition dollar, and make sure that the municipality’s demolition activities yield the greatest benefit to the community and its residents.

- EPA’s Large-Scale Residential Demolition site has a number of resources related to controlling contaminants during demolition and examples of demolition practices. It also provides a detailed Residential Demolition Bid Specification Development Tool.

- HUD’s Resource Exchange’s Demolition Toolkit, which Community Progress helped produce, has a number of useful resources including: a Sample RFP for Demolition Contractors, detailed and basic versions of HUD, NSP, and the Demolition Process, and an Example Survey Form for Demolition Site Inspection. While these tools were developed for the Neighborhood Stabilization Program, many of the tools are applicable outside of that program.

- Annie E Casey and Johns Hopkins University outlined good demolition practices following a study they conducted on lead exposure and demolition in Baltimore.

Have all systems, documents and specifications in “ready to go” status at all time.

It is important to minimize turnaround time for putting out bids, executing contracts and pulling permits. It is best to have a “default spec” in place for each different type of demolition, with a series of alternatives available for clearly defined situations. For example, the default spec could provide for deconstruction soft stripping; in some cases, however, that may not be necessary, and an alternative spec could be available, with clearly defined conditions under which it can be used.

Make sure capacity to carry out demolitions is available.

While most municipalities contract out all demolition work, some have found that creating in-house capacity to carry out all or some of their demolition needs is cost-effective and productive, particularly if the municipality has good managerial/supervisory staff, and employee productivity is not impeded by regulations or contracts.

Where the municipality contracts out demolition work, the municipality should create pre-qualified pools of demolition contractors. This should include both small and large contractors. Including small contractors allows more business to flow to locally based and minority- or women-owned firms, as well as allowing for greater volume of single-family demolitions. Unless the pool is small, bids should be invited on a rotating basis; i.e., a smaller number of firms are selected from within the pool to be invited to bid on each contract.

Firms in the pool should be carefully monitored. If firms do not submit bids on repeated occasions, or firms do not perform timely and high-quality work, they should be removed from the pool. Similarly, the municipality should open up the pool to new firms on a regular basis.

Some municipalities bid individual buildings or packages of buildings, while others issue fixed quantity contracts based on square footage, dollar amount or other criteria.

Set up efficient legal systems to get demolition approval and maximize cost recovery.

In most communities many of the buildings that the municipality demolishes are owned by private parties. In order to make sure that the municipality can take care of these buildings in a timely fashion, the municipality should identify the most efficient process for getting the needed approvals to demolish privately-owned buildings. In some states, this may require going to court to get a court order, but it others it can be done administratively. For example, the State of Illinois allows municipalities to step in and board, repair or demolish certain properties without a court order if the building is three stories or less in height and is a “continuing hazard” to the community.1 The City must provide notice of its intent to demolish by posting on the property, publishing in a local newspaper for three consecutive days, and by certified mail to any person or persons with a current interest in the property. So long as any interested party does not file a written objection, the municipality may demolish the property 30 days after notice is mailed or after the last day of publication, whichever is later. The property must be demolished within 120 days.

At the same time, the municipality should prepare in advance to take advantage of any opportunities it may have for recovering the cost of demolition from the property owner. See Code Compliance for a discussion of cost recovery strategies.

Address material removal and disposal issues constructively.

Disposal of demolition debris is both a major cost item and a significant environmental issue, adding to the nation’s already excessive waste stream. While deconstruction – the careful or systematic dismantlement of buildings in such a way that the individual building components are separated and preserved for potential reuse – is useful in some circumstances, it is unlikely to be a solution for the entire problem of material removal and disposal in communities with widespread vacancy.

Cities should balance the pros and cons of landfill disposal, material separation and recycling and deconstruction to find the most cost-effective and responsible system. This includes working with contractors and landfill operators to find the most cost-effective disposal solutions consistent with state regulations. Regulations and fees (e.g., tipping fees which are the cost to dispose of material in a landfill) vary widely from community to community, as such the cost/benefit calculation for waste diversion strategies will vary. This is also an opportunity to shape state law or local practices to incentivize more environmentally sound practices.

Leave the demolition site in good shape for the future.

The demolition specs should ensure that when the contractor leaves the demolition site, the vacant lot is improved to a level where it is not going to harm its surroundings and subsurface conditions are suitable for any likely reuse of the property (e.g., proper grading and removal driveway aprons and basements or foundations).

Site treatments should also be included in a demolition spec, which could include installing low-mow native ground cover all the way up to a higher-touch treatments including fencing or rain gardens, for a variety of vacant land treatments see the lot guides in our Vacant Land Stewardship Online Resource Center. The site treatment should be scaled to the immediacy of reuse and neighborhood needs. It is more cost-effective and timely to have the work done as part of the demolition contract than to come back months later and have it done as a separate contract.

[1] 65 ILCS 5/11-31-1(e).