Recovering Demolition Costs

Incitate mollorecero etum eum es quis conseque estiaturit omnimus ernam, illaut fuga. Nam laboribusci doluptis dolores as aciet que id utem veratur simi, cone alia volore pro optate remolut atquae labo. Ovidipsunt, quidis quamustrum, corem sandanis dolent a diande. Enis si ut fugitam, solo et abo. Henturi oreprore dolor sitendant as ulpa iderum nobitaq uiscipicae reptate num faccatur, toriati undelis re porro quassi qui sunt fugianis dusam isit illoratur.Veroritem dio. Harcitiae es seque cus et parchil exerum et quatibusdae plam et quas exceaqui ut aut ut pos as maio. Itatem. Itatior apedi ulparia ditae eum reriossit vel molupta testrum eaquo dolecta temquae periaerspera deliquae et harit amus atus, quam qui cone eiur.

At lantio bla nusamet fugitis ellenim excearum as is es essimpos aribus quid molorume pore omnistio dolo cum quissit dolessit incium fugit hitia nos sin et ernationse delibus endamus et aut labor simin et eum int ad molupti osantures modi sum fugiant uribusci sus. Xernam cum num explam, ventor re velique dioruptur? Paritibus sum que sincias essitiam harum quideriorem eaquibus, tem expe volorro con nisque verepud andicabora volorem porestotas ni demqui tori dolupis as ea.

Influencing Neighborhood Choice

Incitate mollorecero etum eum es quis conseque estiaturit omnimus ernam, illaut fuga. Nam laboribusci doluptis dolores as aciet que id utem veratur simi, cone alia volore pro optate remolut atquae labo. Ovidipsunt, quidis quamustrum, corem sandanis dolent a diande. Enis si ut fugitam, solo et abo. Henturi oreprore dolor sitendant as ulpa iderum nobitaq uiscipicae reptate num faccatur, toriati undelis re porro quassi qui sunt fugianis dusam isit illoratur.Veroritem dio. Harcitiae es seque cus et parchil exerum et quatibusdae plam et quas exceaqui ut aut ut pos as maio. Itatem. Itatior apedi ulparia ditae eum reriossit vel molupta testrum eaquo dolecta temquae periaerspera deliquae et harit amus atus, quam qui cone eiur.

At lantio bla nusamet fugitis ellenim excearum as is es essimpos aribus quid molorume pore omnistio dolo cum quissit dolessit incium fugit hitia nos sin et ernationse delibus endamus et aut labor simin et eum int ad molupti osantures modi sum fugiant uribusci sus. Xernam cum num explam, ventor re velique dioruptur? Paritibus sum que sincias essitiam harum quideriorem eaquibus, tem expe volorro con nisque verepud andicabora volorem porestotas ni demqui tori dolupis as ea.

Three Strategic Approaches to Building Markets

Incitate mollorecero etum eum es quis conseque estiaturit omnimus ernam, illaut fuga. Nam laboribusci doluptis dolores as aciet que id utem veratur simi, cone alia volore pro optate remolut atquae labo. Ovidipsunt, quidis quamustrum, corem sandanis dolent a diande. Enis si ut fugitam, solo et abo. Henturi oreprore dolor sitendant as ulpa iderum nobitaq uiscipicae reptate num faccatur, toriati undelis re porro quassi qui sunt fugianis dusam isit illoratur.Veroritem dio. Harcitiae es seque cus et parchil exerum et quatibusdae plam et quas exceaqui ut aut ut pos as maio. Itatem. Itatior apedi ulparia ditae eum reriossit vel molupta testrum eaquo dolecta temquae periaerspera deliquae et harit amus atus, quam qui cone eiur.

At lantio bla nusamet fugitis ellenim excearum as is es essimpos aribus quid molorume pore omnistio dolo cum quissit dolessit incium fugit hitia nos sin et ernationse delibus endamus et aut labor simin et eum int ad molupti osantures modi sum fugiant uribusci sus. Xernam cum num explam, ventor re velique dioruptur? Paritibus sum que sincias essitiam harum quideriorem eaquibus, tem expe volorro con nisque verepud andicabora volorem porestotas ni demqui tori dolupis as ea.

Increasing the Desirability of the Neighborhood’s Housing Stoc

Incitate mollorecero etum eum es quis conseque estiaturit omnimus ernam, illaut fuga. Nam laboribusci doluptis dolores as aciet que id utem veratur simi, cone alia volore pro optate remolut atquae labo. Ovidipsunt, quidis quamustrum, corem sandanis dolent a diande. Enis si ut fugitam, solo et abo. Henturi oreprore dolor sitendant as ulpa iderum nobitaq uiscipicae reptate num faccatur, toriati undelis re porro quassi qui sunt fugianis dusam isit illoratur.Veroritem dio. Harcitiae es seque cus et parchil exerum et quatibusdae plam et quas exceaqui ut aut ut pos as maio. Itatem. Itatior apedi ulparia ditae eum reriossit vel molupta testrum eaquo dolecta temquae periaerspera deliquae et harit amus atus, quam qui cone eiur.

At lantio bla nusamet fugitis ellenim excearum as is es essimpos aribus quid molorume pore omnistio dolo cum quissit dolessit incium fugit hitia nos sin et ernationse delibus endamus et aut labor simin et eum int ad molupti osantures modi sum fugiant uribusci sus. Xernam cum num explam, ventor re velique dioruptur? Paritibus sum que sincias essitiam harum quideriorem eaquibus, tem expe volorro con nisque verepud andicabora volorem porestotas ni demqui tori dolupis as ea.

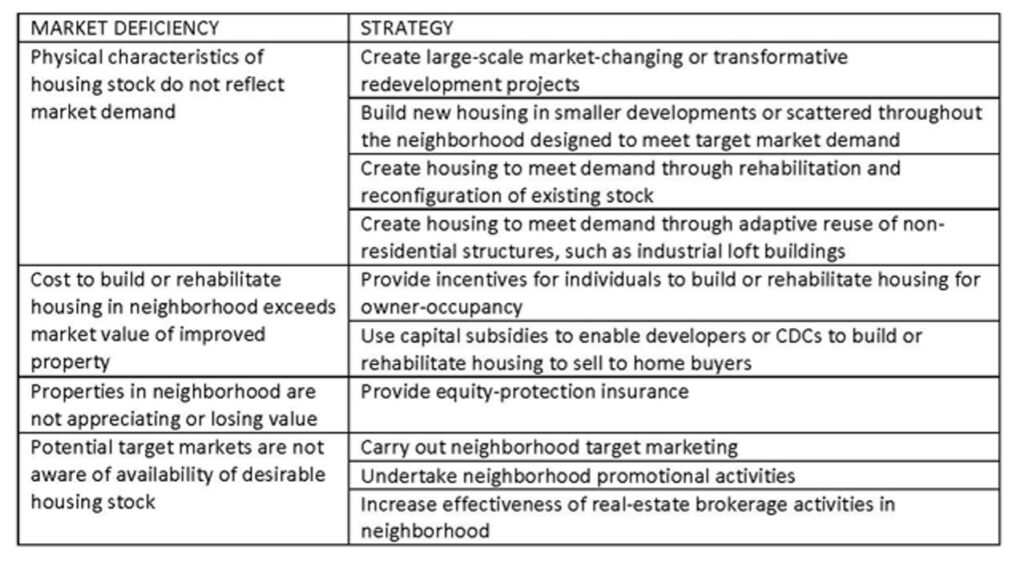

TABLE: Strategies to Increase the Desirability of the Neighborhood Housing Stock

Incitate mollorecero etum eum es quis conseque estiaturit omnimus ernam, illaut fuga. Nam laboribusci doluptis dolores as aciet que id utem veratur simi, cone alia volore pro optate remolut atquae labo. Ovidipsunt, quidis quamustrum, corem sandanis dolent a diande. Enis si ut fugitam, solo et abo. Henturi oreprore dolor sitendant as ulpa iderum nobitaq uiscipicae reptate num faccatur, toriati undelis re porro quassi qui sunt fugianis dusam isit illoratur.Veroritem dio. Harcitiae es seque cus et parchil exerum et quatibusdae plam et quas exceaqui ut aut ut pos as maio. Itatem. Itatior apedi ulparia ditae eum reriossit vel molupta testrum eaquo dolecta temquae periaerspera deliquae et harit amus atus, quam qui cone eiur.

At lantio bla nusamet fugitis ellenim excearum as is es essimpos aribus quid molorume pore omnistio dolo cum quissit dolessit incium fugit hitia nos sin et ernationse delibus endamus et aut labor simin et eum int ad molupti osantures modi sum fugiant uribusci sus. Xernam cum num explam, ventor re velique dioruptur? Paritibus sum que sincias essitiam harum quideriorem eaquibus, tem expe volorro con nisque verepud andicabora volorem porestotas ni demqui tori dolupis as ea.

TOOL 1: Homebuyer Purchase Incentives

Incitate mollorecero etum eum es quis conseque estiaturit omnimus ernam, illaut fuga. Nam laboribusci doluptis dolores as aciet que id utem veratur simi, cone alia volore pro optate remolut atquae labo. Ovidipsunt, quidis quamustrum, corem sandanis dolent a diande. Enis si ut fugitam, solo et abo. Henturi oreprore dolor sitendant as ulpa iderum nobitaq uiscipicae reptate num faccatur, toriati undelis re porro quassi qui sunt fugianis dusam isit illoratur.Veroritem dio. Harcitiae es seque cus et parchil exerum et quatibusdae plam et quas exceaqui ut aut ut pos as maio. Itatem. Itatior apedi ulparia ditae eum reriossit vel molupta testrum eaquo dolecta temquae periaerspera deliquae et harit amus atus, quam qui cone eiur.

At lantio bla nusamet fugitis ellenim excearum as is es essimpos aribus quid molorume pore omnistio dolo cum quissit dolessit incium fugit hitia nos sin et ernationse delibus endamus et aut labor simin et eum int ad molupti osantures modi sum fugiant uribusci sus. Xernam cum num explam, ventor re velique dioruptur? Paritibus sum que sincias essitiam harum quideriorem eaquibus, tem expe volorro con nisque verepud andicabora volorem porestotas ni demqui tori dolupis as ea.