New York State Land Banks

A New National Standard

Topic(s): Land Banks, State & Local Analysis

Published: May 2017

Geography: New York

Author(s): New York Land Bank Association, Center for Community Progress

For a more up-to-date review of land banks and the land banking movement in New York, see A Decade of Progress: Celebrating 10 Years of Land Banks in New York (February 2023).

The land bank movement in New York traces back to Albany’s passage of the 2011 Land Bank Act. Five years later, New York boasts one of the most active, sophisticated networks of land banks in the country. Currently, 20 land banks operate across the state, from Buffalo to Long Island. New York land banks have guided more than $130 million in private and public investments into the transformation of hundreds of vacant, abandoned, and tax-delinquent properties to productive use in support of community priorities.

By all measures, the land bank movement in New York has exceeded even the most ambitious expectations. This report offers a history of the land bank movement in New York, including an assessment of the work completed to date, the factors key to success, and what to expect of this maturing movement in the years to come.

The Underlying Economic & Systemic Causes of Vacancy and Blight in New York

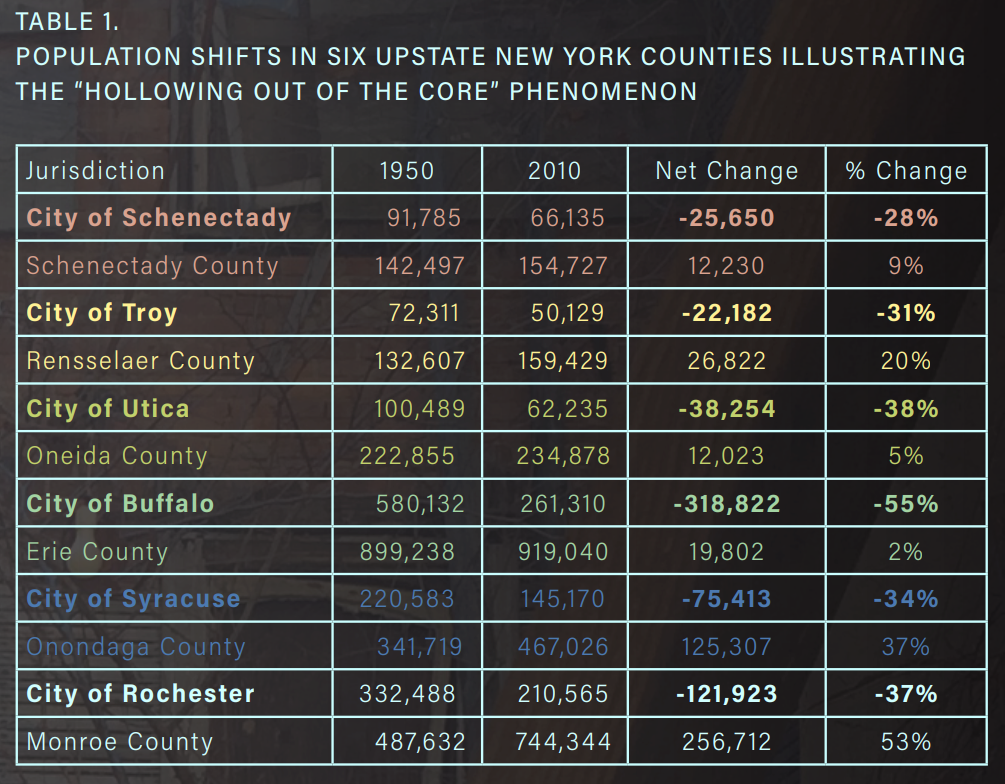

Many cities, towns, and villages across New York endured significant population losses over the last fifty to sixty years (see Table 1), and suffer the challenging dynamics that stem from an oversupply of housing. In fact, these population losses often occurred while their county or overall region experienced growth, which illustrates the need for local and county leaders to work collaboratively at the regional level to tackle the negative impacts imposed by problem properties.

This significant market imbalance of supply and demand for housing is a key reason why many New York communities have wrestled with large inventories of problem properties for decades. And it’s under these weak housing market conditions when other barriers and challenges, legal and functional, become more obvious and onerous.

For instance, many local governments lack a solid understanding of the systemic causes of vacancy or abandonment, or even the scope, scale and characteristics of the inventory of problem properties in their community. Most local governments maintain parcel data in silos, exhibit little inter-departmental collaboration, or have such antiquated data systems that systematically integrating parcel data to analyze trends and identify problem properties early is very difficult.

Additionally, the legal systems that can help prevent or minimize the harms of vacancy and abandonment—code enforcement systems, property tax enforcement and foreclosure systems, and mortgage foreclosure systems—can often be ineffective or inefficient, making it difficult to stop and ultimately reverse the decline of neighborhoods burdened by an oversupply of housing, weak housing markets, and concentrated poverty. In fact, the weaker the housing market, the more the deficiencies in these key legal systems can actually contribute to the problem.

For example, local governments in New York rely heavily on the criminal prosecution of property owners to enforce housing and building codes. However, out-of-state owners and limited liability corporations (LLCs) can easily evade the reach of the courts, making it difficult to hold these specific owners accountable. As most local and county governments in New York auction off properties that are tax-delinquent, problem properties in distressed neighborhoods often default to local governments in the absence of any bids, or are scooped up by these same speculators or irresponsible landlords for pennies on the dollar in cash deals, perpetuating the cycle of decline. Since the markets in these chronically disinvested neighborhoods do not inspire investor confidence, many of the successful bidders on these low value properties will “drain” rental property of any remaining equity, and then simply walk away.

Over the last fifteen years or so, forward-thinking leaders in New York have experimented with approaches to minimize the harms caused by problem properties, with a focus on some of the key systems discussed above:

DATA SYSTEMS AND MANAGEMENT PRACTICES: More and more cities are partnering with county governments or local colleges and universities to rethink data collection and information management systems, recognizing that reliable and accurate data must be the starting point for all strategic decisions, particularly the allocation of limited resources.

CODE ENFORCEMENT SYSTEMS: Many cities have passed vacant property registration ordinances and launched new rental registration programs. Many local governments also step in to abate a nuisance on a private property, and then roll the costs to the tax bill as an effective collection strategy.

TAX ENFORCEMENT SYSTEMS: Some communities have changed how they enforce delinquent taxes, such as discontinuing the sale of tax liens or creating special auctions for first-time home buyers only.

Some local governments have also cultivated deep community relationships, building up civic capital to help transform vacant spaces into vibrant places, such as parks, community gardens, or green stormwater infrastructure. Meanwhile, a decade’s worth of New York State programs, from the Restore NY Grant Program to the Regional Economic Development Councils, have brought hundreds of millions of dollars to New York communities, allowing local leaders to fund blight elimination programs that address their own unique and urgent needs.

While these have been helpful, incremental steps in the right direction, the underlying economics of some neighborhoods—and the steady outmigration of residents—continue to pose a threat to the health, vitality, and safety of too many New York families and residents. In the face of these persistent challenges, there has been a growing awareness among state and local leaders that an effective approach to problem properties requires more than just a few tweaks to our existing tools and laws. There also need to be new tools, determined political leadership at all levels of government, regional planning, deeper collaborations across sectors, data-driven decision making and investment strategies, and a recurring and diverse funding strategy.

The Land Bank Movement Emerges in New York

As early as 2007, a handful of New York State leaders, motivated by the impressive results of land banks in other states (notably Michigan and Ohio), began to advocate for legislation allowing local governments to create land banks to complement and bolster existing blight prevention efforts.

After three years of educating state officials about land banks and building a network of supporters across the state, Assemblyman Sam Hoyt, Assemblyman William Magnarelli, and Senator David Valesky—the bill’s primary sponsors—finally saw the New York State Land Bank Act signed into law by Governor Cuomo on July 29, 2011. The original legislation allowed for the creation of up to ten land banks through a competitive application process managed by the Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC). In 2014, both legislative chambers unanimously supported increasing the number of potential land banks from 10 to 20. By the end of 2016, ESDC had approved all 20 land banks. As outlined in the legislation, land banks are nonprofit organizations formed by local government and subject to further oversight by public authorities law.

The powers granted to land banks under New York’s law intends that these new public entities have the ability to streamline the removal of vacancy and abandonment and create a nimble, accountable, and community-driven approach to returning problem properties to productive use. The Land Bank Act represents what Frank Alexander, cofounder of and Senior Legal and Policy Advisor at Community Progress, describes as the third generation of land banks in his Land Banks and Land Banking publication (2015, second edition).

In fact, between 2012 and 2014, seven more states passed land bank bills that shared similarities with New York’s third generation land bank legislation. A total of eight communities submitted applications to ESDC across two rounds (Spring 2012 and Winter 2012/2013) and all eight were approved. The first group of approved land banks represented diverse geographies and interests: two local jurisdictions, four single counties, and two regional entities. Two more, Albany County and the City of Troy, were approved in the summer and fall of 2014. ESDC accepted applications on a rolling basis after the first ten were approved, and another ten land banks had been approved by the end of 2016.

Support from CenterState CEO and Community Progress helped land bank staff and board members cultivate a strong peer-to-peer network that involved monthly conference calls and an active email listserv. By 2014, this loose support network had evolved into a formal professional organization, the New York Land Bank Association (NYLBA).

NYLBA offers legal and policy guidance to all members, develops annual legislative priorities, boasts a successful track record of legislative advocacy (see Section 4: Going Forward), and hosts an annual summit dedicated to sharing best practices and exploring more effective crosssector solutions to the challenges posed by problem properties. NYLBA currently has 14 duespaying members and is operated by a volunteer board of directors. According to Community Progress, NYLBA is one of the nation’s most sophisticated and effective statewide land bank associations.

Funding the New York Land Bank Movement

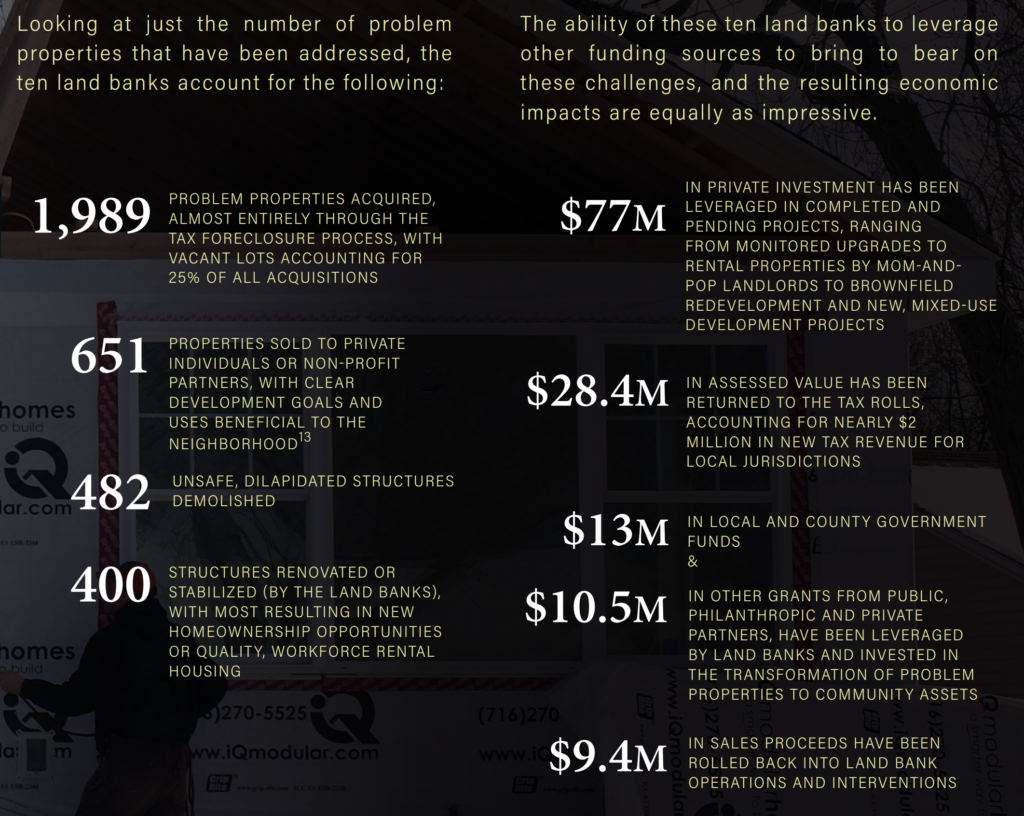

Based on national research, land banks typically rely on local funding (general fund appropriations from county and local governments), sales proceeds, a portion of the property taxes generated from repurposed properties, and grants from the philanthropic, public, and private sectors. The same is true of land banks in New York. At the time of this report, 12 of the 20 land banks reported cash commitments from local or county governments totaling more than $13 million to date. More than $9 million in sales

proceeds has been rolled back into land bank activities. An additional $10.5 million was reported in grant awards secured through federal and state programs and local philanthropic partners.

However, most of the funding support for New York land banks to date has come from the New York Attorney General’s (AG) Office. About one year after ESDC’s approval of the first round of land banks, the AG’s Office announced in the summer of 2013 a new source of dedicated funding for land banks. The AG’s Community Revitalization Initiative (CRI) would competitively award $33 million over two rounds in 2013 and 2014 to eligible land banks. The funds were part of the first National Mortgage Settlement, which NY Attorney General Eric Schneiderman had a key role in securing, and the AG’s office promised that carving out dedicated funding for land banks would be explored in future settlements.

The first round of CRI funding saw the allocation of $13 million in awards among eight land banks in the fall of 2013. Nearly all land banks requested grant funds to hire dedicated staff, but there was a lot of innovation and variety among the placespecific proposed activities. For instance, Suffolk County Land Bank requested and received funds for Phase I and Phase II environmental assessments for brownfields

that a recently completed local planning initiative identified as key next steps. Chautauqua County Land Bank’s award went almost exclusively to fund an aggressive demolition program (80 properties). Newburgh Community Land Bank requested funds to support the acquisition, remediation, and stabilization of tax-delinquent properties to support the City’s goals of adding quality workforce housing.

By the time the second round of funding was announced in July 2014, land bank applications from Albany County and the City of Troy had been approved by ESDC and were eligible to apply. Table 4 includes a summary of the total amount of grants awarded through CRI. The AG’s Office carved an additional $20 million for land bank support out of subsequent settlements with lending institutions in 2016. Managed by Enterprise Community Partners and LISC, these funds were competitively awarded to the 19 land banks that were eligible at the time of the grant application deadline.

These settlement funds have been critical to the early successes of New York land banks. As the next section makes clear, the public investments made to date offer a compelling case that, when provided reliable and recurring funding, New York land banks can successfully intervene in this cycle of disinvestment, remove the financial and legal barriers that make these properties unmarketable, attract responsible private investment, and help advance a community’s tailored approach to achieving healthier, more vital, and safer neighborhoods for all.

Measure of Success: By the Numbers

By nearly any measure, the work carried out by New York land banks has been a resounding success, especially when considering these organizations have been up and running for less than four years. But, while land banks have certainly benefited from outstanding leadership, an effective professional association (NYLBA), and strong support from state and local officials, the influx of dedicated funding from the AG’s Office has been critical in jump-starting the land bank movement statewide. The metrics featured in this section are based on the ten land banks that received CRI funding from the AG’s Office, since the remaining ten have been in operation for less than a full year (as of December 2016).

Measure of Success: The Unseen Benefits

Performance metrics don’t convey the full story of how land banks help improve a community’s economic, social, and fiscal health. First, problem properties drain local tax dollars—primarily in the provision of fire, police, and code enforcement services—deter private investors, and reduce the values of adjacent properties, directly harming the equity and potential wealth of innocent neighbors.

A recent report by the Community Impact and Innovation Unit of the NY AG’s Office estimates that land bank interventions supported by CRI funding have saved $19 million in property value for surrounding homes. For every problem property acquired, maintained, and then returned to the private market for productive use, that is one property that no longer generates these external costs and liabilities. The net fiscal gain to local governments is even greater than the amounts above indicate.

Second, there is anecdotal evidence that eliminating these problem properties, particularly unsafe structures, has qualitative impacts that advance social justice and equity goals. Most of this work occurs in many of our most distressed neighborhoods in New York, and these investments signal to residents—who for too long might have felt left behind—that they deserve healthy, safe, and vibrant neighborhoods. Research shows that land bank interventions, particularly demolitions and greening vacant land, can reduce crime rates in the immediate vicinity. And even if these interventions don’t show a significant correlation to reduced crime, field surveys before and after show that residents feel safer. The ultimate goal is to support vibrant and healthy neighborhoods for all, and incremental investments that improve perceptions of safety and neighborhood pride are the first step.

Finally, when land banks work more closely with local governments, and strategically align with other preventative systems and revitalization efforts, a shift in community expectations as to what defines responsible ownership can yield significant gains that might go unnoticed. For example, in Syracuse, the City had stopped enforcing delinquent taxes for nearly seven years because it had neither the capacity nor desire to own and maintain the most distressed properties that would end up in the City’s inventory at the end of the foreclosure process. Collection rates decreased, given some unscrupulous owners realized there would be no consequence for not paying taxes.

When the Greater Syracuse Land Bank formed, it agreed to accept all properties that ended up in foreclosure if the City again started to enforce delinquent taxes. City officials acknowledge that , between November 2012 and June 2015, this new approach resulted in the collection of an additional $7.2 million in delinquent city taxes, and $2.75 million in delinquent county taxes. Officials estimate that when the backlog of delinquent tax cases is fully addressed, which is expected to occur in 2017, the on-time collection rate of property taxes in the City of Syracuse will have jumped from 94% to 99%.

Download the report to read local impact stories »

Conclusion

New York communities, particularly the urban centers and rural villages upstate, have long struggled to minimize and reverse the negative impacts of vacancy and blight. At times, the scope, scale, and complexity of blight has seemed overwhelming. But with the state’s land bank movement maturing and expanding, there is reason for optimism. Not even five years old, the state’s land bank movement has proven the value of breaking from the status quo, and taking a more proactive, deliberate and community-driven approach to vacancy and abandonment . And as state and local leaders look to evaluate and gauge the return on early rounds of public investments, the evidence is clear: $7 7 million in private investment leveraged to convert liabilities to assets; $28 million in assessed value returned to the tax rolls; and tens of millions saved in homeowner equity and future local tax dollars because nearly 2,000 problem properties have come under the thoughtful stewardship of community-based land banks and no longer threaten the health, vitality, and safety of neighborhoods.

The credit doesn’t belong to just a few. Just as fighting vacancy and abandonment requires a coordinated, sustained, and comprehensive approach, so too must the credit for the gains these first five years be distributed among many parties: From forward-thinking state leaders who pushed through the enabling legislation in 2011 and then supported a series of legislative reforms, to passionate local practitioners who invested a great deal of resources and time in launching the first round of land banks; from local elected officials who, despite budget challenges, saw the value in investing in land banks, to the Attorney General’s office, which carved out tens of millions of dollars from various settlement agreements to support early land bank efforts; from land bank and land-use experts providing support to ensure land bank success in New York, to the resilient residents and local nonprofits who, in partnership with land banks, remain determined to reclaim the health, vibrancy, and security of their neighborhoods.

The maturing land bank movement in New York , moving from follower to leader in just five short years, represents one of the biggest success stories in the national field of practice. With 20 land banks in operation across the state, from Buffalo to Long Island, communities are waging a smarter, more proactive fight against blight , adapting these new tools to local needs, and finding ways to complement existing blight prevention strategies.

There is a long road ahead, but thanks to the state’s maturing land bank movement, and a growing network of local and state leaders who recognize the need for ongoing public investment in this critical work , there is every reason for optimism in New York’s revitalization work.

Topic(s): Land Banks, State & Local Analysis

Published: May 2017

Geography: New York

Related Publications

Other Related Content

Subscribe to join 14,000 community development leaders getting the latest resources from top experts on vacant property revitalization.