What Causes “Urban Prairies” in Shrinking Cities?

June 13, 2023

From Smaller Cities in a Shrinking World: Learning to Thrive Without Growth Copyright © 2023 Alan Mallach. Reproduced by permission of Island Press, Washington, D.C. It has been edited for blog format.

If the one common feature of shrinking cities is population decline, it would follow that vacant properties should be the most direct consequence, as fewer people need fewer houses, stores, and workplaces. But it’s far from that simple. While vacant properties are a challenge in shrinking cities around the world, the blocks of devastation or the “urban prairies” of US cities like Detroit or Gary, Indiana, are rarely found in shrinking cities elsewhere, except perhaps as the result of the purposeful demolition of large-scale housing projects in the United Kingdom or eastern Germany.

As cities become “thinner” and their land is used less intensively, their physical environment changes, and once-urban land becomes available for other uses or reverts to nature, as has famously happened in Detroit and a cluster of other American cities. Vacant properties and declining public services can all discourage people from moving in and promote moving out, leading to still more shrinkage.

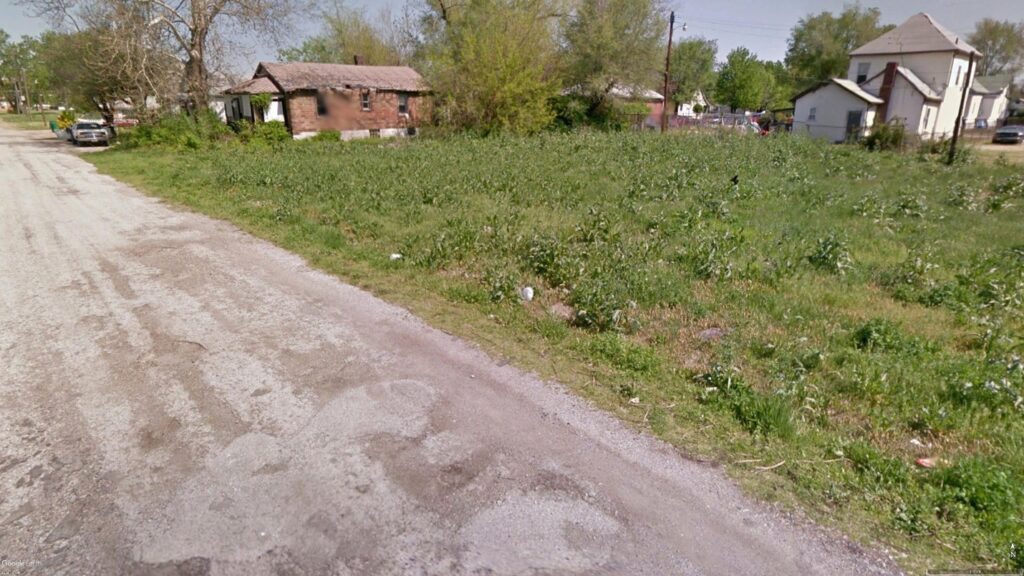

In the most extreme cases, as in some American cities that have lost over half of their one-time population, a rising tide of vacancies can lead to the wholesale abandonment of entire neighborhoods. Neighborhoods, however, are rarely if ever abandoned entirely. Instead, they take on a bizarre quasi-pastoral quality, in which open fields are interspersed with houses, some vacant and some still occupied, as in East St. Louis, a struggling small city in Illinois across the Mississippi River from St. Louis. East St. Louis has lost over two thirds of its population since 1950.

Similar images regularly appear in American writing on shrinking cities. Detroit is most often the subject of those pieces. As writer and Detroiter John Gallagher has put it, Detroit’s “most striking characteristic is the vacant feel of the city, those ghost streets with just one or two houses left, those expanses of what Detroiters long since have taken to calling ‘urban prairies.’” The same is true of parts of Cleveland, Gary, Flint, and many other places. Two questions come to mind. Why do urban prairies happen, and why are they so much a US, rather than a global, phenomenon?

To answer those questions, we must go back to the changes in American cities that began with the White flight of the 1950s and 1960s, driven by racial and economic disparities in ways not seen elsewhere. At the end of World War II, most Black residents of American cities lived in segregated ghettos. It is appropriate to call them that since, much like the Jewish ghettos of early modern Europe, their existence was enforced by outside pressures, both formal and informal. Although many cities had a solid Black middle class who lived side by side in the ghetto with lower-income and poor families, Black households were on the whole much poorer than White households in the same cities, while they were subject to all of the insidious forms of racial discrimination that characterized midcentury America.

After the war, as White flight was emptying out large parts of the cities, Black populations grew as a result of the Second Great Migration. As thousands of Black families moved or were pushed into the neighborhoods being vacated by White flight, the Black community bifurcated economically and spatially. While Black families of all income levels had by necessity shared the segregated places to which they had previously been relegated, from the 1950s on their paths diverged.

The bifurcated movement of Black families out of the ghettos created strong Black neighborhoods in some places, but also large swaths of racially segregated, highly concentrated poverty. These areas were devalued economically and disinvested by both public and private sectors. Properties lost value, lenders became increasingly reluctant to lend, and municipal services deteriorated. Landlords who could not collect enough rent to get a reasonable return on their properties began to walk away, while homeowners or their heirs increasingly had difficulty finding buyers for their homes. People who could moved out, while fewer moved in.

The outcome was predictable. Populations declined far faster in areas of concentrated poverty than elsewhere in the same city. As populations decline, the number of vacant houses and vacant lots eventually reaches levels at which the real estate market effectively ceases to function. Homeowners move away or die, fewer and fewer of their homes find buyers, and more and more stay empty. The few people who want to buy them find it hard to get mortgages or insurance. Owners give up, walk away, and stop paying property taxes, and increasing numbers of properties revert to public ownership for nonpayment. In the end, beleaguered municipalities, seeing no alternative, demolish these properties, gradually creating the urban prairies of today’s shrinking cities.

Between 2014 and 2020, the city of Detroit demolished nearly 20,000 vacant properties, mostly single-family homes, adding to the nearly 100,000 vacant lots already dotting the city, the result of earlier demolitions stretching back decades. But demolitions never kept pace with the continued weak demand for the city’s houses and the continued outflow of population. Between 1990 and 2010, over 70,000 housing units were removed in Detroit, mainly through demolition, but at the end of that period the city had 40,000 more empty units—not counting the increase in vacant lots—than at the beginning.

Demolition is nothing new. But in recent decades, buildings by the thousands have been demolished in American cities with no idea of what possible use might be made of the vacant land that would result. While some proponents of demolition, in a form of magical thinking, argue that removing vacant buildings will stabilize distressed neighborhoods and put them on the path of revival, in the final analysis it is about eliminating surplus buildings for which there is no visible market demand. Practitioners of demolition often hope, though, that if the housing inventory is reduced in that fashion, a city might eventually reach a point where supply and demand are in reasonable balance, and properties will no longer be abandoned. One Rustbelt politician has called it “thinning the herd.”

Whether supply and demand are likely to come into balance in any city will depend more on how the larger forces of economic growth and migration are playing out in that city than on demolishing buildings. In the meantime, the effects of demolition, as it creates gap teeth in once-intact street walls or scattered houses amid stretches of vacant land, can as easily undermine rather than catalyze potential market revival. Where lack of demand and depressed prices make it economically unfeasible to restore abandoned buildings, though, one can reasonably ask, “What is the alternative?”

While at one level a vacant housing unit is a vacant housing unit, how it affects people’s lives and the social construction of their neighborhood can be very different if it is a derelict house in the middle of a densely built neighborhood or a vacant apartment in a hulking ten-story building at the edge of the city. The tolerance for vacancy, in the sense of the extent to which vacancies can take place without triggering significant social decline, is likely to be much higher in the latter. Imagine the destructive effect on a neighborhood if one out of four of its houses are empty. The visible effect of a 25 percent vacancy rate in high-rise apartment buildings may be far less. Not that there is no effect, though, not least on the ability of the remaining owners to maintain their building.

Allowing derelict buildings to remain in place does nothing but harm to a neighborhood; as a Cleveland homeowner who lived next to such a building told a community advocate, “I don’t care what you do. Fix it up or tear it down. But do something!” There is no good answer. But it is possible, as we look to the future of these cities, that the vacant land that is now accumulating may become a valuable resource in their efforts to become sustainable communities.

Purchase a copy of Smaller Cities in a Shrinking World from Island Press.

Subscribe to join 14,000 community development leaders getting the latest resources from top experts on vacant property revitalization.