Topic(s): Delinquent Tax Enforcement, Projects and Events

Efficient property tax collections vs. the cult of homeownership

October 5, 2013

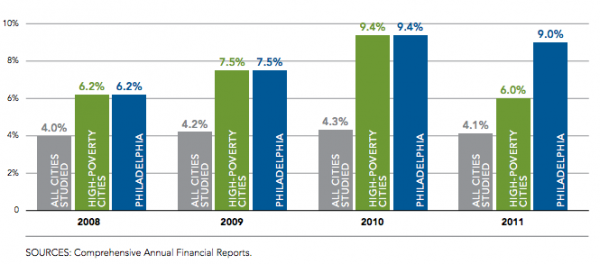

The rate of tax delinquency in Philadelphia versus other cities studied by the Pew Charitable Trusts.

Cross-posted from Next City, this article is part of the 2013 Reclaiming Vacant Properties Conference liveblog series. Check out all the in-depth content — even if you weren’t able to join us in Philadelphia from September 9-11, 2013, you’ll feel like you did!

This morning’s session “Making the Case for Efficient, Effective and Equitable Tax Foreclosure Reform” raised key questions about equity considerations in tax foreclosure reform, but largely elided some difficult questions about how our national political obsession with homeownership interferes with our ability to efficiently collect the revenue needed to fund public services.

The focus was property tax collections in Philadelphia, a city notorious for its property tax delinquency epidemic. Thomas Ginsberg of Pew’s Philadelphia Research Initiative horrified the audience with embarrassing collections statistics from PRI’s recent report on this problem.

Philadelphia’s delinquent property owners are half a billion dollars in arrears. About 15 percent of delinquent property owners are on a payment plan, and they account for 11 percent of the total unpaid bills. Even when people get on a payment plan, the default rate is higher than 30 percent. As a comparison, Pittsburgh’s default rate is under 15 percent.

Ginsberg qualified this with the observation that high-poverty cities do tend to have higher median same-year delinquency rates, but rates in other high-poverty cities like Atlanta and Milwaukee are much closer to the national median. And despite having a shorter, one-year timeframe for collection action than some other Pennsylvania counties that string things out over two years, Philadelphia’s redemption rate is severely worse.

The big takeaway was that, even while some dysfunction is caused by arcane state laws governing tax foreclosure, the high level of discretion in Philadelphia’s administration of payment plans is a key reason why its collection rates are so much worse than in other Pennsylvania municipalities.

Why is there so much discretion in Philadelphia? The reasons are numerous, but I would argue that one important factor is the heretofore lack of differentiation in city politics between low-income people who actually can’t afford to pay their bills, and the deadbeat landlords, speculators and “investors” who owe 59 percent of the unpaid bills. The high level of discretion and the loosey-goosey enforcement are thought to protect the former group, but actually end up protecting the latter.

Speculators are easy enough to demonize, but it’s also worth singling out the cult of homeownership in U.S. politics for some blame here, too.

While it’s certainly not the fault of low-income or elderly people that they can’t afford their property tax bills, it is a big problem that city governments can’t collect on the full amount of revenue these properties are supposed to generate.

It’s revenue that goes toward providing critical services that schoolchildren, low-income people, disabled people and others depend on. It may seem like the equitable course of action to play it extra loose with tax enforcement, but the people shortchanged by this policy also have a strong — some would even say stronger — equity claim on those resources.

What does this have to do with homeownership promotion policies? Because people too poor to afford their property tax bills should probably rent housing and not own it. In a multifamily rental property, the landlord spreads the property tax bill across a few different households, keeping things affordable for each household.

In the United States though, renting is stigmatized not just on a normative level, but as a matter of policy. The federal government provides large subsidies for homeownership (primarily through the mortgage interest deduction, but also through sundry other housing, tax, transportation and land use policies) and a pittance for renters.

Over many years this has led to massive underinvestment in rental housing, which in turn makes it a problematic political proposition to glibly suggest homeowners who can no longer afford their tax bills should sell their homes and rent instead. Rent what? Philadelphia has enough trouble as it is facilitating the development of enough affordable rental housing for the growing population of young upwardly mobile renters, let alone lower-income people and those on fixed incomes.

Subscribe to join 14,000 community development leaders getting the latest resources from top experts on vacant property revitalization.