Topic(s): Projects and Events

A 341-page blight-fighting plan requires a lot of teamwork

June 23, 2015

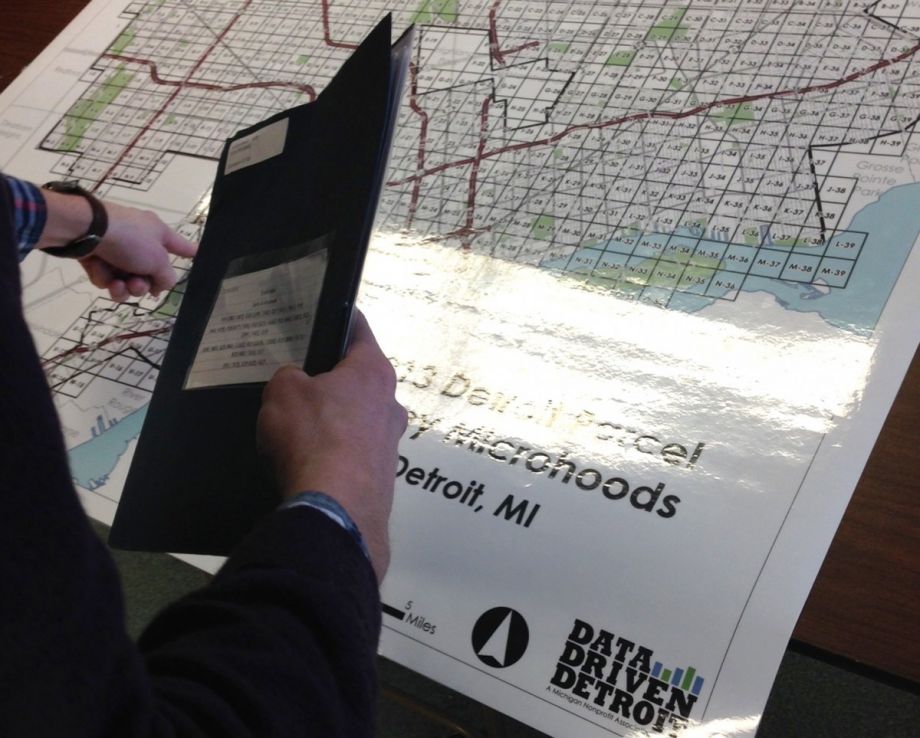

The Detroit Blight Removal Task Force has used a data-driven approach in eliminating blight. (AP Photo/Corey Williams)

Cross-posted from Next City, this article is one of a ten-part series inspired by the 2015 Reclaiming Vacant Properties Conference.

Three hundred and forty-one pages and 235.5 megabytes. That’s the length and size of the Detroit Blight Removal Task Force plan, published last year. Based on a survey of the city’s 380,000 parcels, the task force found some 85,000 of them blighted, making strong, widely reported recommendations such as reform to tax and title transfer procedure, and the demolition of 40,000 structures.

Blight is not something new to American cities, nor is the study of it. But, the events of recent years, especially the foreclosure crisis, have inspired policymakers and community development professionals to go about blight mitigation differently. From Cleveland to New Orleans, in the last five years or so, data-driven blight reduction frameworks have been hatched. The approach continues to catch on in cities around the U.S.

“I’m certainly seeing an uptick of [planning and framework proposals],” says Danielle Lewinski, vice president and director of Michigan initiatives for the Center of Community Progress, on the trend. “Could be due to the increase of vacancy or blight. It also could be due to the increase of availability or accessibility of data.” Lewinski adds that initiatives are being hatched to help departments and organizations that are essentially underfunded considering the problem’s magnitude.

“One of the core intents of a blight elimination plan really should be trying to better coordinate existing capacities and resources,” says Lewinski.

The Detroit Blight Removal Task Force is one model for such all-encompassing collaboration.

The task force essentially started with three people: Detroit Schools Foundation President Glenda Price, U-SNAP-BAC CDC Executive Director Linda Smith and billionaire businessman Dan Gilbert. They weren’t quite sure where to begin.

Deb Dansby, a VP at Gilbert’s Rock Ventures company, explains that the toll of property deterioration and abandonment was obvious, but the path toward properly eradicating those dilemmas was less clear. Price, Smith and Gilbert quickly recognized that they needed more perspectives, and so their table welcomed another 13 partners from the private, public and volunteer sectors.

“They had one meeting as the three of them, and then from then on it really became that larger working group 90 percent of the time,” Dansby recalls. “Everybody just looked at each other and said, nobody in the room is an expert on this, and nobody in the country is an expert on this at the scale that we have to deal with in Detroit. So it was a pretty quick epiphany that we needed to gather as much information as we can on what is going on already in [the city] … . How do we get smart about it before we ever try to solve it?”

This graphic represents how they organized their collaborative information collection process.

(Credit: Detroit Blight Removal Task Force/Rock Ventures)

Building a caucus of sorts was Detroit’s first step. One of Dansby’s responsibilities for the task force was to serve as a point person, corresponding with groups as they worked among themselves, checking to make sure their efforts stayed coordinated.

Also, as the term blight is often used flexibly, an early challenge for the task force was defining it. Here’s what they settled on: Any building or lot that was on the city’s demolition list, “open to the elements and trespassing” and those “exposed to the elements, are not structurally sound, are in need of major repairs, are fire damaged, or have essentially been turned into a neighborhood dumping ground,” would fall under the blight category. Those pegged as displaying “blight indicators” were abandoned parcels or property owned by a government-sponsored enterprise or government itself. All partners conducted their research with these definitions in mind.

Two collaborators, Data Driven Detroit and Loveland Technologies, created Motor City Mapping, the citywide survey that introduced the country to the new term blexting, and recruited the public to help with creating a comprehensive database of blight. (Using smartphones, Detroit residents can blext — a mashup of blight and text — photos of the properties they see.) The survey was completed in just nine weeks during the winter of 2013-2014 (an awful one, if you recall).

The speed and inclusivity of the endeavor overall are things that make Lewinski gush, but corporate world veteran Dansby downplays these aspects.

“Just bringing that private sector model into something that the public sector has to deal with benefits any of these projects,” says Dansby. “That’s really all we did. It wasn’t anything crazy new or innovative. It was just different than the way these projects typically worked.”

Subscribe to join 14,000 community development leaders getting the latest resources from top experts on vacant property revitalization.