What is the cost of blight? What new research from Atlanta tells us

February 26, 2016

What is the cost of blight?

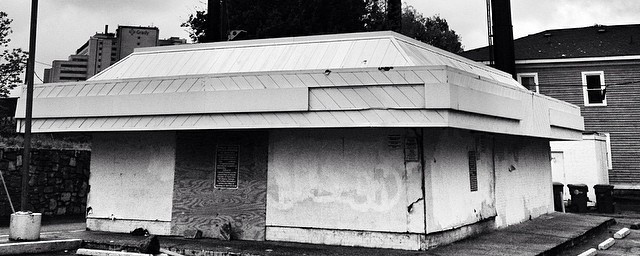

We know that vacant properties cost cities through lost property tax revenue, and that they also bring down the property values of surrounding homes in the neighborhood. We know that cities have to spend considerable funds on activities like mowing lots or boarding up abandoned structures. Vacant properties also often attract criminal activity, and are vulnerable to arson and accidental fires, all of which impact the city’s bottom line.

Even with all of this knowledge, however, pinpointing the exact cost of blight to a city can still be a challenge. Often times the data may not be easily accessible or accessible at all. If data is coming from different departments, it may use different measurements and be difficult to compare and synthesize. Blight affects many aspects of community wellbeing, so conducting a cost of blight study has to be an interdepartmental effort. Government siloes, therefore, can be particularly difficult roadblocks.

Despite—and in some ways because of—the effort they involve, cost of blight studies can be an incredibly powerful tool. If we can’t specify the impact of vacant properties on municipal coffers, then we can’t effectively make the argument for municipalities, and their state and federal counterparts, to invest heavily in blight remediation.

And the process of compiling accurate data on blight and vacancy itself can have a long-lasting impact in terms of making local government more efficient and effective. By bringing together different data sets, and working to make those data sets directly comparable, cities tap into a wellspring of information about property conditions. For example, a city might bring together the fire department’s incident records, the county treasurer’s tax foreclosure records, and the code enforcement department’s records of citations, and create a common metric, ensuring that all of these systems, for example, use parcel identification numbers rather than street addresses or vice versa.

That information can eliminate redundancies and yield insights that make tracking the costs of vacancy and blight much easier moving forward—for example, encouraging multiple departments to include a uniform data point on incident reports describing whether or not a property at the heart of that incident is vacant. If police and fire departments, as well as code enforcement departments, track vacancy status, then documented patterns often emerge that allow leaders to determine whether and how much a vacant property costs the taxpayer, and to make the case for appropriate resources to reduce those costs.

Many city leaders can point anecdotally to the one vacant property that is constantly the source of police and fire calls and unheeded code violations. But without consistent recorded data—and cross-departmental data that is recorded and speaks in the same municipal language—we cannot determine whether and to what extent vacant properties all over our communities similarly cost taxpayers more and in what order of magnitude.

Dr. Dan Immergluck, professor of urban and regional planning at Georgia Tech, authored a new report looking at the cost of blight in Atlanta, which, even in the study’s conservative estimate, still numbers many millions of dollars. We interviewed him to learn from his experience conducting Atlanta’s cost of blight study. Here are his responses:

In your research into the cost of blight in Atlanta, what struck you as most important or surprising?

Dr. Dan Immergluck (DI): While I assumed that the costs of vacant and distressed properties to the City were substantial, I didn’t have a good handle on how large they might be. Annual service costs at Police, Fire, and Code Enforcement agencies alone amounted to approximately $3 million per year. Lost property tax revenues due to decreased home values added another $2.7 million annually. Then, when we looked at overall losses in home values, the lost wealth was over $150 million.

Why is this cost of blight study valuable for Atlanta? Why do you think cost of blight studies in general are useful tools?

DI: The findings suggest that interventions to address these properties should have large returns for taxpayers and homeowners, especially in low- and moderate-income neighborhoods. These interventions might range from targeted demolition for the most distressed properties to strengthened, strategic code enforcement efforts.

What is the role of interdepartmental cooperation in determining the cost of blight?

DI: It’s critical. Several departments need to provide key data for this kind of study. It is important for each agency to identify one (or sometimes more than one) point person who understands the agency’s data systems and will work the researcher doing the study. It is also critical that city leadership is committed to the project to ensure that all the agencies cooperate.

What advice would you give to local government leaders hoping to undertake a similar study?

DI: A key step is to identify whether city has the essential data needed to conduct the study. If a city does not, and wants to consider a study down the road, it will need to work with a potential researcher to understand how it needs to change its data systems to collect the necessary data.

Subscribe to join 14,000 community development leaders getting the latest resources from top experts on vacant property revitalization.